A year ago, in May 2022, I chose Last Call as my Sculpture of the Month, with its message about our impacts on Mother Nature (after whom the month of May happens to be named). This year, I skipped the May SOM to focus on interviewing several of the artists in my recent, collaborative, Silicon Valley Open Studios art show.

But now, as we enter the month of June, named after the Ancient Roman goddess Juno, who is associated with the life of women in love, marriage, and childbirth (i.e. women’s part in human survival), I was drawn back a decade, to 2013 and the sculpture below, Choosing the Path of Least Extinction.

This piece alludes to an additional question: Not only, “Can nature survive the impacts of humans?” But also, “Can we humans survive those impacts as well?”

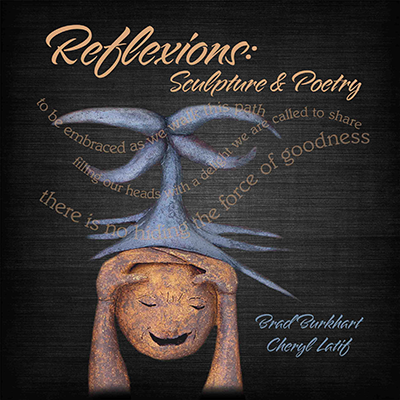

Choosing the Path of Least Extinction

Interestingly, although humans have been around for over 300,000 years, we’ve nearly gone extinct several times. Those of us who survive today descend from a gene pool smaller than a few troops of chimpanzees! Such narrow genetic diversity makes us much more vulnerable to fundamental changes in climate and ecology than other species with greater genetic variability. (1)

Throughout most of human history, birth rates and moderately growing numbers had little impact on our planet’s resources. Although, humans may have played a major role in the extinction of most large mammals during the most recent period of mass extinction that ended the Pleistocene era, about 10,000 years ago. (2) More recently, however, our human population began to grow significantly, first with the transition from hunting to farming, and then exponentially in the 1500’s with the emergence of the industrial revolution.

It’s hard to believe, but twice as many people live on the earth now as in 1968, and we do so (in very broad-brush terms) in greater comfort and affluence because of how much our species has managed to extract from the environment. (1) We have monopolized available resources. Currently, our species sequesters 25 to 40 percent of all the organic matter that plants create out of air, water, and sunshine. (3) The rest sustains all other species.

Only 5% of the world’s lands are unaffected by humans: 44% is low modification, 34% is moderate, 13% is high, and 4% is very high impact. (4) Due to a lack of habitat and sustenance, scientists estimate that 25% of all species are actively threatened with extinction because of human activities. Wild animal populations, including insects, have decreased dramatically (by over 58% between 1970 and 2010). (5)

Not surprisingly, our current dependence on fossil fuels has also added to these losses because of unsustainable climate warming.

Our effects on the biosphere may also be impacting our own species’ survival, as well. Human reproduction rates have dropped worldwide due to a combination of lower sperm counts in men, the increased stress of modern life, environmental pollution, and women choosing to bear children later in life or not at all.

Ecologists use the term “extinction debt” (1) to describe a situation when a species has so destroyed its present habitat that it has guaranteed its future extinction. It’s unclear whether humans have reached this threshold, but at the very least, we appear perilously close, and our decreasing numbers may indicate that we have already crossed over.

So Choosing the Path of Least Extinction poses two options:

- “Do we want to continue along our current path, with the highest species extinction rate since the history of our planet, perhaps leading to our own extinction?“

- Or, “Knowing that we now live on the brink of the extinction debt limit, can we evolve a way of life compatible with a longer timeline before we disappear?”

The sculpture itself may offer up some guidance…

We appear to be looking at an indigenous person whose culture has lived in close harmony with nature. She appears to be in consternation about her place in our present world, which burns in the background, perhaps due to climate change. On her belly, she bears a symbol that may represent the potential for future generations.

In the air above, a crane — the oldest bird species on the planet — flies like an omen, offering up the wisdom of survival through many changes. And behind her, an ostrich stands witness.

Like humans, the ostrich evolved in Africa, has two strong legs, and is unable to fly. Although known jokingly for sticking its head in the sand as a sign of avoidance, what ostriches actually do when threatened is turn inward, hiding their long neck and wings under their body to become like a rock, since they cannot fly away. This reminds us that we cannot fly away from our impacts on the Earth and need to turn inward for redirection.

It is thought that if an ostrich appears in a dream, it symbolizes that we’re avoiding something important. Might we be avoiding necessary changes, ones imbued with the survival wisdom of the crane, that will allow us to create a future for humans and other beings here on Earth?

Some may say, leave this to the next generation, but I believe we need to act now, and we have only one choice: to Choose the Path of Least Extinction. Otherwise, we could pass beyond the extinction debt limit, and no longer exist as a species at all!

I’d love to hear your thoughts on the matter. How do you think humanity should proceed?

References

- Henry Gee, “Humans Are Doomed to Go Extinct,” Scientific American Newsletter, November 30, 2021

- Hannah Richie, “Did humans Cause the Quaternary Megafauna Extinction?” Our World in Data, November 30, 2022

- University of Michigan, “The Flow of Energy: Primary Production to Higher Trophic Levels,” October 31, 2008

- Nicholas LePan, “Visualizing the Human Impact on the Earth’s Surface,” Visual Capitalist, November 20, 2020

- World Wildlife Fund, “69% average decline in wildlife populations since 1970,” October 13, 2022