Here is a review of my first show at the Unitarian Church of San Diego Art Gallery in 1995 from the San Diego Reader. Hope you enjoy it.

Watch Out, Rover!

‘There are deep affinities between primitive or

archaic mythical imagery and the delusions of

what recall madness”

Review

Twentieth Century Iconography

Jonathan Saville

San Diego Reader

9/15/1994

There is an unusual show of terracotta reliefs by Brad Burkhart at the Bard Hall Gallery of First Unitarian Church in Hillcrest. The local artist is willfully out of step with the fashionable trends of contemporary art. His vision is essentially religious, and although he subscribes to no particular sectarian dogma, there is an explicit content to his religious view of human existence.

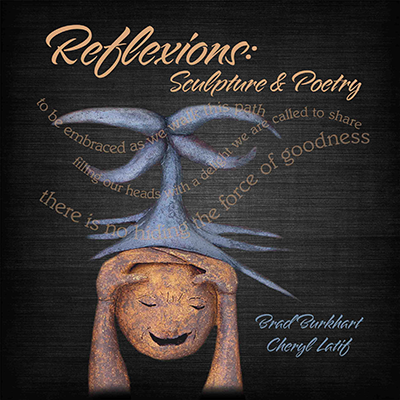

Birth of Aphrodite

Burkhart sees human beings as undivided essences comprising both mind and body, and humanity and nature as unified in the same way. The artistic consequence of this transcendence of dualism is a pervasive spiritualization of material substance, which is especially significant since Burkhart has chosen as his medium an extremely hard and solid material, baked clay. The medium is treated so as to underline materiality. The sculpted figures on these small rectangular panels are often in very high relief. Bold plastic forms stand out against patterned textural backgrounds, with these “naively” stylized signs for fur, feathers, water, or rock frankly presenting themselves as lines, strokes, or pinpricks incised in clay.

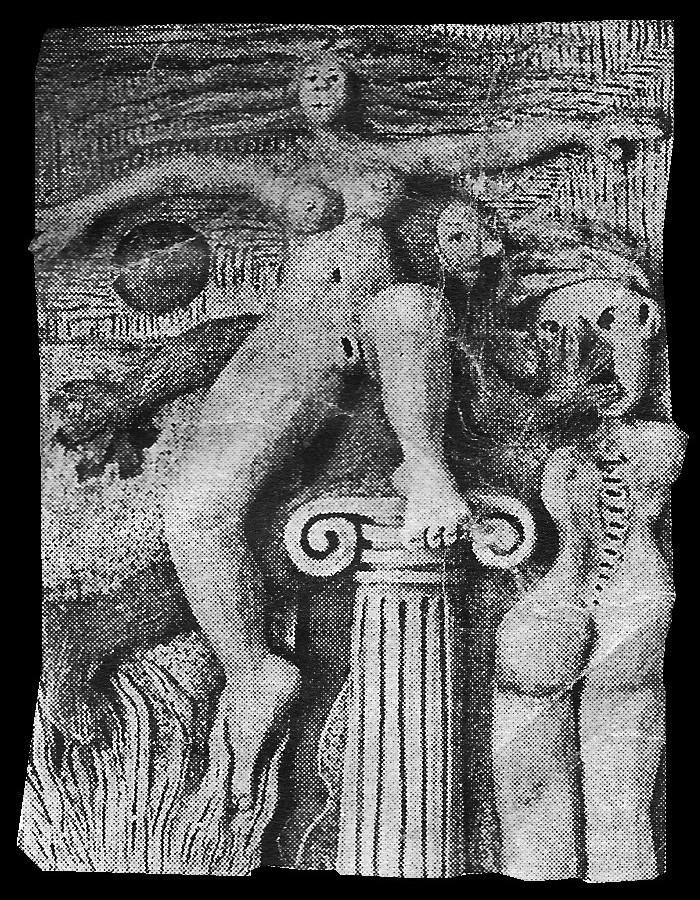

Exile from Atlantis

The spirituality is in the choice of images. Here, Burkhart relies in an eclectic way on the

non-Western artistic traditions, taking cues from Paleolithic cave paintings, Native American art,

Hindu sculpture, and the archaic periods of Greece and Rome.

At the same time, he seeks to rediscover universal spiritual reality by exploring his own unconscious. In a procedure akin to the automatic writing of the surrealists, he begins with free pencil drawings removed as much as possible from conscious control. The resultant lines and forms generate their own images, which his conscious artistic mind then defines more precisely, as well as subjecting them to aesthetic refinement. The drawings (some of which are included in the show) are then translated into the plastic language of clay. The process thereby moves from unconscious perception of universal archetypes through the inherited iconography of varied religious traditions, to permanent embodiment in the material objects we can see on the gallery walls.

In looking at these terracotta plaques, therefore, we are expected not only to delight in the artist’s inventive use of his medium, but also to go beyond the terracotta to the underlying numinous presences the images represent. In a certain sense, these are icons, whose mysterious evocations (for it is rarely easy to decipher them explicitly) are meant to stimulate our imagination and propel us toward integrative spiritual experiences of our own.

As for the artistic imagination that serves as midwife to such experiences, it is wild, uninhibited, playful, primitive, childlike, and—in appearance, at least—sometimes schizophrenic (for there are deep affinities between primitive or archaic mythical imagery and the delusions of what we call madness). Burkhart shows us animals and fantastic creatures (often treated with whimsical humor), nude erotic images of men and women, rituals, angels, amazons, Kali, Humpty Dumpty, the sun and the moon—everything representational, nothing realistic, all belonging to a fantastical world Burkhart wishes us to take as more real than the one we dwell in.

Grounding

The effect of these sculptures at the gallery, arrayed with aesthetic acumen by the artist himself, is cumulative, so that all of them together produce an effect of a rather different order from the contemplation of individual plaques. It may be helpful, however , to glance at a few

Grounding characteristic images—such as Burkhart’s Birth of Aphrodite. That she has something to do with the Olympian goddess is indicated by the Ionic column, but this is not the shapely, sensuous, civilized Aphrodite of Greek and Roman sculpture, but a primitive female fertility image (tiny head, huge lower body, crudely prominent breasts and genitals) in a form going back to 30,000 BC. One of her feet is planted firmly on the column, as though to indicate how her archaic magical function surmounts its later, elegant embodiments.

The rest of the panel’s iconography is more obscure and hence more tantalizing. Behind this monument of physicality and sexuality with her streaming, Bacchante-like hair, there lurks a jester in lower relief and in side view, one of his splayed hands on the face of another female (armless, her head turned around 180 degrees on her neck, and her shoulder and hip jutting out from the plaque’s edge). Without further clues, we must allow our imagination to rove. Is there some mockery here of classical sculpture as too remote from its original impulses, a skewed Venus de Milo at the mercy of the irrepressible irony of the flesh?

No unimpeachable explanations are forthcoming. Nor are we given any explicit help in identifying the fabulous furry-scaly creature of Grounding, lying helplessly on its back as though out of its element, its paws grasping at nothing, its huge spiral eye and gaping mouth expressing amazement or fear. Beneath it, there lies an equally confounded fish. Do the incised parallel lines along the upper border represent rain, which has flooded the sea and washed these primeval aquatic animals on shore? Is it the great deluge of worldwide mythology? Whatever the meaning (or meanings, for they are no doubt multiple), there is something at once grotesque, comical, and pathetic about the displaced creatures, a hint of absurdity, a hint of anguish, something we can identify with in the dark cellars of collective memory….

There seems to be a related theme in Exit from Atlantis, where the separation into two levels (articulated by horizontal bars of different textures) presumably narrates the sinking of the fabled island beneath the sea. Above, two individuals who may be a cross between human beings and birds appear to be fleeing; below, a naked woman has already drowned—or is she a natural-super-natural fish-woman of the deep, looking up triumphantly at her imminent victims?

In these works, clues to meaning are often fo be found in the titles and in recognizable references to familiar mythologies and iconographies. But there are a number of Burkhart’s pieces to which no such clue is given, and which might plausibly be interpreted as fanciful representations of quite normal, quite nonspiritual realties. My favorite instance of this mode is Dance of Old Rover, in which a huge, benign, furry dog is being petted and mauled by three violently exuberant children, who clutch his head, tongue, neck, ear, and paw, while, tongue lolling, he patiently endures this treatment.

A charming family scene, we might think, the kids play with old Rover on the rug. Yet there is nothing in Burkhart’s work that does not suggest dangerous or exalted overtones, and in this expertly composed and textured panel, I am struck by a kind of demonic ferocity in the romping infants, a sign (perhaps) of children’s proximity to those primitive energies of fundamental reality that are capable of lifting us into ecstasy or ripping us to shreds.

Dance of Old Rover

Ambiguities of this sort are to be found everywhere in the Burkhart exhibit, which, while offering a good deal of immediate aesthetic pleasure, at the same time demands of its viewers an unprejudiced imagination and a willingness to remain in uncertainty. That is what you need for a religion without doctrine, a vision without objective evidence, a spiritual truth that exists as both the One (in the nature of things) and the Many (in each individual psyche)